Oltre 12 mila pmi italiane hanno scelto di diventare venditore Amazon

Nell’era degli “Amazon addicted”, lo stato di salute del s...

- The stronger economic cycle is boosted by a favourable EU economic context and robust tourism

- The economic impact of the debt crisis involving Croatian giant the Agrokor Group has now been contained

- EU membership and the goal of euro accession support Croatia’s fiscal consolidation and sound macroeconomic policies

- External debt is high but rapidly decreasing

- The government coalition is fragile, which hinders reforms

- Unresolved territorial disputes contribute to strained relations with neighbours

The Croatian economy is boosted by a strong EU economic cycle, despite Agrokor’s debt crisis

The Croatian economy is continuing to enjoy strong momentum after a six-year recession between 2009 and 2014. Since 2015, economic activity has gradually recovered and accelerated to a solid 3% on average in the past two years, driven by strong tourism activity (the top source of export revenues), private consumption and investments. The economic climate is very supportive for the Croatian external sector as it benefits from the positive EU economic cycle. Without supportive domestic reforms, real GDP growth is forecast to slow down to an average of 2.5% by 2022.

Still, GDP has not yet recovered to the pre-crisis level and a few downside risks are clouding the outlook. In the short term, one risk comes from Agrokor’s insolvency, declared in 2017. The retail and food giant, burdened by heavy debt and hidden financial losses, was unable to repay its creditors in spring 2017. So far, the crisis has had a contained economic impact thanks to the strong economic context. Given Agrokor’s substantial economic weight – it had a 14.7% GDP contribution in 2015 – the State has bailed it out and started its restructuring, which is expected to end by September 2018 and potentially include debt-equity swaps with banks. A more pronounced impact cannot be ruled out as the restructuring of Agrokor and its subsidiaries could lead to collective dismissals and harm consumption and investment. It could also hit the “euro-ised” banking sector via an increase in the NPL (non-performing loans) ratio, which continued to decrease to 12.5% in Q3 2017. As a result, banks, which are broadly well capitalised and maintain moderate credit growth, have increased provisioning related to the Agrokor debt.

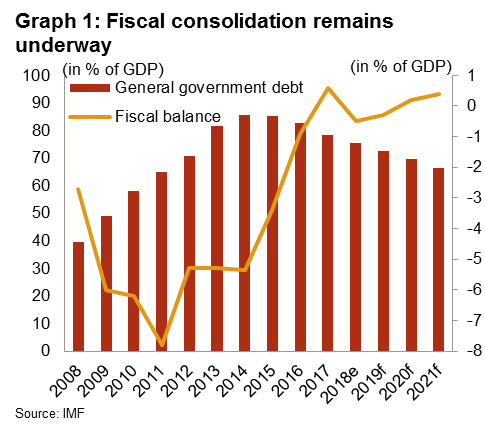

Fiscal consolidation supported by EU membership amid structural weaknesses

The Croatian economy suffers from structural weaknesses that could hamper long-term growth and productivity. At the top of the list are the brain drain and poor competitiveness resulting from high wages, labour market rigidities and a wide economic role for mainly inefficient and fiscally costly SOEs. Yet, all in all, the outlook remains buoyant for the economy as it will further benefit from its EU membership – e.g. through increased access to EU markets – and will continue economic convergence with the euro area in order to adopt the euro by 2020. This process will further improve Croatia’s macroeconomic fundamentals. This is most obvious for fiscal policy, which will further benefit from fiscal consolidation and European structural and investment funds. Public finances have long been a major economic risk for Croatia. Indeed, after the 2008 crisis, successive deep budget deficits were recorded and public debt more than doubled to 85.8% of GDP in 2014. As from 2016, the budget was brought close to balance and high public debt has been on a declining path, allowing the EU to close the excessive deficit procedure for Croatia in June 2017. In the coming years, fiscal balance and public debt (78.4% of GDP in 2017) are forecast to head towards a small surplus and less than 70% of GDP as of 2020 respectively.

Public debt nevertheless does not include substantial contingent liabilities from SOE guarantees. Moreover, the fragile government coalition and large public administration make deeper and bolder fiscal reforms hard to implement.

Croatia has had a comfortable balance of payments and a large current-account surplus since 2012. This external position is partly explained by a successful tourism industry and increasing merchandise exports to the EU (despite a small export base) since EU accession. The monetary policy is accommodative with low interest rates and inflation – expected at 1.2% this year – whereas the kuna exchange rate is being kept stable as it will continue to fluctuate close to the euro until the 2020 target is met.

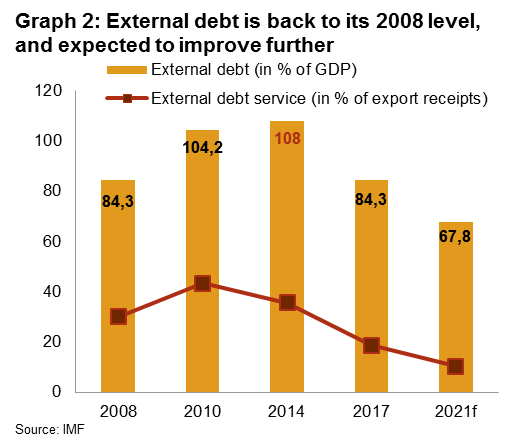

External debt elevated but rapidly decreasing

Croatia’s highest MLT political risk factor and vulnerability to shocks lies in its external debt, which rose sharply in 2008-2009. However, between 2015 and 2017, reduced borrowing and rising GDP brought the external debt-to-GDP ratio down to a still high 84.3% (from a peak of 108% in 2014). This swift decline is forecast to continue towards 65.8% by 2022. As a result, the debt service-to-export revenues ratio collapsed from 40.2% in 2012 to 18.7% in 2017. It is expected to drop to a more sustainable 11.3% this year before stabilising around 10% thereafter.

The external liquidity position is sound and has further improved with the decline of short-term debt from 15% of current-account receipts in 2015 to a low 10.2% in June 2017. Foreign exchange reserves are robust at a comfortable 7 months of imports as a result of strong exports and large capital inflows including EU structural funds. Therefore, all in all, favourable economic developments and deleveraging have allowed the financial risk to go down considerably in two years. Further improvement is expected in the future.

Improved government stability, persistent regional tensions

Croatia’s current government is moving forward through hilly territory. In essence, the ruling coalition, which is led by PM Plenković, is fragile as it is composed of two ideologically disparate parties (i.e. the centre-right HDZ party and the centre-left HNS Party) and has a thin parliamentary majority which relies on support from minority representatives and independent MPs. The failure of two no-confidence motions in Parliament in six months has nevertheless strengthened the prospect of government stability until the 2020 parliamentary polls. Still, alleged government mishandling of the Agrokor debt crisis and the narrow parliamentary majority sharply hinder its economic policy and bold reform plans (e.g. public administration, privatisations, fiscal consolidation). Moreover, government policies are opposed by the majority of the population and face vested interests from big companies which collude with political elites.

Regional tensions with neighbouring countries have never completely gone since the end of the Yugoslav Wars and continue to largely dominate Croatia’s external policy. Tensions remain high due to still open wounds and unresolved territorial disputes with neighbouring countries. Recently, the prospect of 2019 presidential elections has led the Croatian President to take a more nationalist stance, thereby fuelling tensions with Bosnia notably after the ICTY ’s conviction of six Bosnian Croats of war crimes last November. The decision was severely rejected by the Croatian government as it de facto meant Croatia’s shared responsibility in the Bosnian War. Besides, relations with Serbia remain the most potentially destabilising. Examples have abounded in recent years, such as temporary import tariffs or trade blockades at the border between the two countries to stop migrant flows through Serbia. Also, the building-up of the military in Serbia is leading Croatia to imitate its neighbour at great cost. That said, their bilateral relations are in no way comparable to what they were in the mid-90s. Renewed tensions tend to be more diplomatic, especially given Croatia’s EU and NATO membership, which contribute to greater stability. A recent official meeting between the two presidents to address bilateral issues, notably the border dispute along the Danube, is a positive sign of goodwill to improve future relations, which is in Serbia’s interest given its EU accession candidacy.

Fonte: Croazia

Oltre 12 mila pmi italiane hanno scelto di diventare venditore Amazon

Nell’era degli “Amazon addicted”, lo stato di salute del s...

Oltre alla bassa capacità di spesa, le condizioni applicate dalle banche per l’accesso a finanziamenti, hanno un impatto sulle performance del settore.

Dopo una performance brillante nel 2017 con una crescita di 31 miliardi di euro dell’export di beni, le esportazioni italiane continueranno ad avanzare quest’anno de...

While its economy could be progressively stabilising after months of sharper deceleration, Beijing is actively trying to ease trade tensions with the US for an exten...

Nel dibattito sul cambiamento climatico poca attenzione è riservata al ruolo del commercio internazionale. Le potenzialità degli accordi bilaterali e multilaterali –...

Era il 2009 quando Satoshi Nakamoto, nome vero o inventato che sia, ideò la tecnologia Blockchain e la criptovaluta Bitcoin e oggi, dopo dieci anni, la blockchain re...